Of course I’m an academic and writer and it’s my job to convince you (you may already be convinced) that wildfire is important, that thinking about and talking about and studying and making discoveries about and applying discoveries about future fire is important.

These things undeniably are important. And if you are a funder looking for someone to bet on, please contact me at my University of Melbourne email address. Particularly if you work for a philanthropy organisation, a foundation or a business or are a high or ultra-high net worth individual. What may be pocket change to you could change my life and unlock the potential of the Kiln to forge new pathways for all of us towards a sustainable fire future. Seriously, bet on me, you won’t regret it.

But now that I’ve gotten the distasteful elevator pitch out of the way, what if wildfire’s not that important? What if other things are more important?

I’ve already made this point, sort of, by referring to the Black Score as a mere footnote to the collapse of Western Civilisation.

But let me dwell on it a little longer. How do wildfires stack up against other natural disasters?

Per the EM-DAT dataset lovingly plotted over at Our World In Data, wildfire is about an order of magnitude less impactful financially than extreme weather globally. It also lags earthquakes, floods and drought. (It’s much worse than fog though)

Per the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, wildfire did not come close to making the top five natural hazard disasters in 2023, by either fatalities or financial losses. Those dubious honours went to the Türkiya-Syria earthquake in February 2023.

Per our friends at Deloitte Access Economics and the Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience & Safer Communities, bushfire again lags other hazards in terms of costs in Australia: flood, severe storm and hail, and tropical cyclones are at least an order of magnitude most costly than fire. Earthquake trumps it too, although fire does edge out coastal inundation (I suspect this may not be the case for long given the preponderance of stuff we’ve stacked along our coasts, girt not only by sea but also by sea level rise).

Per the National Centers for Environmental Information, fires at least punch above their weight in per-event costs. They still fall well short of tropical cyclones ($23b per event) and drought ($12b per event), but at $6b per event wildfires sit above flooding, winter storms, freezes and severe storms.

Ok, so that’s hazards. What about other risks? What about other stuff that knocks us off our perch?

What about coronary heart disease and dementia including Alzheimer’s disease? What about COVID-19? What about infectious diseases? Cerebrovascular disease and lung cancer? What about suicide, land transport accidents, perinatal and congenital conditions? What about ‘other ill-defined causes’?

What about the food we eat, the water we drink, the air we breathe, the soil our plants grow in?

What about the way we move, the way we sleep?

The way we relate to others, and others relate to us?

What about political, social and economic injustices? What about racism, sexism, transphobia and other harmful forms of prejudice?

What about overwork? Doomscrolling? Screentime?

What about the rare but big stuff? What about existential risks? These are important enough to attract the attention of heavyweights like Cambridge, Stanford and Oxford (at least until the latter closed this year - wonder if they saw that coming?).

Stanford’s Existential Risks Initiative helpfully sums them up in four pithy points:

nuclear war

pandemics, bioterrorism, and other threats related to advances in biotechnology

catastrophic accidents/misuse and other risks related to advances in AI

effects of extreme climate change and environmental degradation

I have to say, the “accidents/misuse and other” combo is doing a lot of work in point number three. A hero of mine, Douglas Hofstadter, confessed to being anxious and depressed about the havoc soon to be wrought by AI. I’m pretty sure he didn’t use the words accident or misuse. I encourage readers to check out the full interview linked to above, but my recollection is that he was talking about a fundamental shift in what it means to be human, in how we relate to the world, in our place in the world.

What about some interplanetary, galactic, or cosmic event?

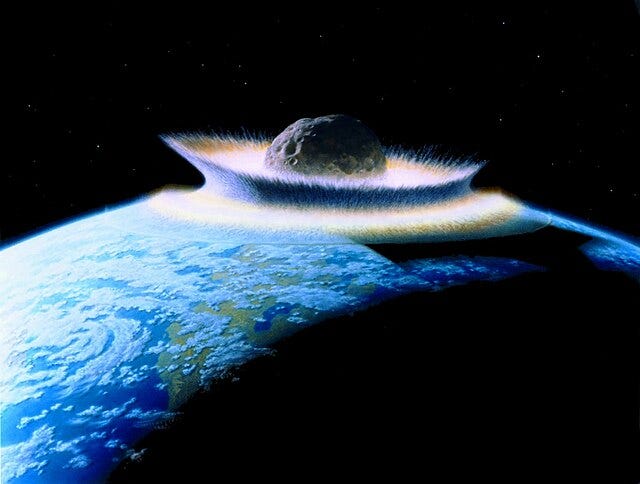

The above picture includes a great quote from the artist commissioned by NASA to produce the image:

A planetoid plows onto the primordial Earth, during the eons of time when conditions were ripe for the development of life. It is possible that life of kinds unknown to us appeared repeatedly only to be destroyed in collisions like this one which could 'rework' the entire surface. Fortunately the average size of debris declined sharply through geologic time, but the supply of wayward rocks a few kilometers in size is by no means exhausted.

Gee, it’s rather hard to put all these things into perspective.

I suppose you could try to memorise all the above numbers. Steep yourself in the wisdom of micromorts (mental note: avoid mountaineering). Perhaps enlist a specialist to tailor them to your own unique bioneurogeopolitical situation.

Maybe you should remind yourself that some threats are low despite being very visible, tangible and salient. You could compare the data on threats with the data on how much effort we spend understanding and reducing them. That might make you angry or sad though, which poses its own risks.

We here in wildfire world go to some lengths to try to measure the impacts of fire on things we care about and the impacts of our attempts to manage it on fire and other things we care about. We even contemplate the benefits (positive risks) of wildfire: scroll down to Table 1 here and feast your eyes on the provisioning, regulating and cultural services rendered by fire. We still have a long way to go. But we’re probably doing much better than many others on that front.

What does your Risk Pyramid look like? Where does fire sit in it? And what does that mean for where we should be directing our efforts?

I gave up thinking about hazards about 20 years ago and moved moved to a consequence focus. Start with the system definition, and then think about the things that might cause the system to bend, buckle or fall over. Its like Cheryl said to Walter, in the Secret Life of Walter Mitty, "my crime writing teacher says, start with the end you want and work backwards" That's what I think we need to do. What's the desired outcome? no deaths? people continuing to lead their lives? We aren't good at describing what want to protect

Hi Hamish...yes it's mostly not fire. The UNDRR hazard profiles list some 8 domains and 300 plus hazards...https://www.undrr.org/publication/hazard-information-profiles-hips...I,my glad your starting to explore the broader context and its potential threats and risks associated through damage or disruption...