Why Fire Is So Hot Right Now

An award-competing long form article about science and our fire predicament

The UK branch of the Conversation recently advertised a writing prize, asking for long form articles with the winner getting to meet with a publisher to discuss a book proposal. Gasp! I have been giving serious thought to writing a book - inspired partly by the rousing [cough] reception to this humble blog - so this seemed like the perfect opportunity to have a crack. Sadly, my crack fell through the cracks, but I’m not too cracked up about it. I shall press on, undaunted.

In the mean time, please enjoy this Quick’n’Ezy, store-bought, pre-prepared post. Long time readers will recognise many of the themes and examples. Note that the images have been added after the fact. Perhaps if I’d bunged them in the entry, I might have fared better.

Why fire is so hot right now

One does not simply wake a sleeping toddler. On the afternoon of October 17, 2013, I was weighing up the risk of disturbing my daughter’s peaceful slumber with the risk of not making it to pre-school in time to collect her older sister. I stared out the window.

The view was different today. Sitting right there, a few ridgelines from our place, was a very large, very thick and very dark plume of smoke. My PhD topic had come home to roost.

Despite the frantic efforts of residents and firefighters, within a few days almost two hundred homes in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney had burnt to the ground.

Eleven years have passed since that day and wildfires are still making headlines for all the wrong reasons. Tragic and devastating loss of life from recent fires in Hawaii, Chile and Algeria. Choking smoke and globally significant carbon emissions from Canada’s boreal forest mega-season in 2023.

Damage to precious Indigenous cultural heritage values. Underinsurance epidemics or worse, the withdrawal of insurers altogether from fire-prone areas. Hundreds of species and ecosystems pushed to the brink by the Australia’s Black Summer fires of 2019-20.

Putting a price tag on these impacts is difficult, if not impossible – but here’s one for starters: around half a trillion dollars a year in the U.S. alone.

In response to these Pyrocenic portents, researchers are rolling up their sleeves:

In fire laboratories, combustion facilities and wind tunnels, we’re probing the physical foundations of fire behaviour.

In the field, we’re teasing apart the mechanisms that dry out live and dead fuel, switching on the flammability of giant swathes of vegetation.

We’re tracing the steps of the epic evolutionary dance between fire and biodiversity.

We’re spying on fire from outer space, witnessing its ebb and flow at continental scales, driven by our planet’s axial tilt.

We’re building forecasts, warning systems and engineering solutions.

Basically, we’re sciencing the s**t out of this.

But as remarkable as all this science is, there’s a problem. Like the faintest scent of something burning in the kitchen, something’s not quite right.

Haven’t we heard this story before? Of diligent scientists ringing the alarm bell about the catastrophic consequences of complex natural systems knocked out of balance (by us) and careening out of control (into us)? And aren’t we still waiting for a happy ending to that other story, despite thousands upon thousands of carefully crafted pages, and decades upon decades of warnings? Doesn’t the carbon dioxide measured at Mauna Loa continue to rise – silently, ceaselessly, ominously?

When it comes to wildfire, we would do well to learn one of the harshest lessons of climate change: that science, as magical as it is, is powerless to drive change on its own.

Science is part of something much bigger, a system made up of words that make a lot of scientists queasy. Words like culture, history, politics and power. And yet baked into much of how we do science, how we teach it and how we talk about it, is the idea that there are science-shaped pieces missing from the great big jigsaw puzzle that is our world, and that our job is to fill these gaps with science.

Some call it the loading dock or linear model of science; Naomi Oreskes calls it the supply side model and points out several questionable assumptions behind it: that people understand us, that they want to listen to us and that the playing field for information about science-relevant topics is a level one.

Sadly, but unsurprisingly, the thorniest, messiest and most pressing problems cannot be solved by just adding science.

Fortunately, there’s a group of people who know all about this. Some of them are even scientists! That’s right, I’m talking about our colleagues down the corridor in the arts, humanities and social sciences.

They’ve been thinking long and hard about the relationship between science, scientists and society (to be fair, many of us natural scientists think about these things too). They’ve been talking about sustainability and there are eery similarities with what we know about fire.

In fact, fire can be read as a microcosm of the whole sustainability crisis:

The world has problems, universities have departments. Even though the strategic plans of every College and University are absolutely saturated with references to multi- and transdisciplinary collaboration, the majority of academics still sit here in our siloes, within Schools, Departments and Faculties. The gravitational pull of these disciplinary boundaries is hard to escape. This is perhaps understandable given the ‘separation of academic powers’ is close to a thousand years old.

Reductionism is potent, but not omnipotent. Breaking reality down into its component parts can be an incredibly fruitful way of studying it. But we need to remember to put Humpty Dumpty back together again. So much research, so much of our education system, is based on isolated problem fragments, stripped of context and doled out in bite sized assignments and projects. Yes, we have to start somewhere and that there are risks to biting off more than you can chew. But what if we’ve accidentally taught ourselves to avoid complexity? As the floodwaters of data and information (and misinformation) rise, we desperately need to invest in review, synthesis and curation (and not just by AI). We need to find ways of stitching all these parts back together into something with depth and coherence; into something whole.

Much of the impact of science stems from work ‘off the side of the desk’. That is, through conversations, meetings and interactions with people. This is not to minimise the importance of publications – peer review remains one of the bedrocks of science and academics won’t get far without a steady stream of ‘outputs’. It’s just that if publications are all we’re doing then we may be selling ourselves short. Academics are overworked as it is so let me make it crystal clear: I am not arguing we should pile more onto the already overcrowded plates of researchers. I’m just pointing to the limitations of a purely publication-oriented approach. And yes, this is self-serving. We wildfire scientists have an unfair advantage with the whole ‘impact agenda’ due to our naturally close links to fire, land and conservation managers.

We need to remember how to embrace experiments if we’re going to find our way out of the mess we’re in. Experimentation is another bedrock of science, yet the whole idea sit uneasily with the leaders of most organisations, be they in academia, industry, government or the not-for-profit sector. No one likes to admit they may not know what they’re doing, that things may not work, or that – gasp – mistakes have been made. But humans actually have a rich history of experimenting with how we live.

In this spirit of experimentation, allow me to conclude with a hypothesis: that the following six ideas might help us think, talk and shape some collective visions about how to live with fire.

Fire is ancient. Mere geological moments after the appearance of plants on land, there was fire. For four million centuries fire has been part of the evolutionary furniture of terrestrial life. Some became besties with it, while others ended up icing fire out. Over much of the earth’s land surface, you simply can’t know biodiversity unless you also know fire.

Fire is global. Thanks to remote sensing, we are now awash with incredible imagery of fire’s global footprint. We can now track fire incidence, area burnt and even rate of spread on every corner of the globe. As we gather more data, we can ask pointed questions like how unusual any region’s current fire season is, and what trends are emerging above the noise of year-to-year variability. Unfortunately, one recently identified trend is an increase in the frequency and intensity of the planet’s most energetically extreme fire events.

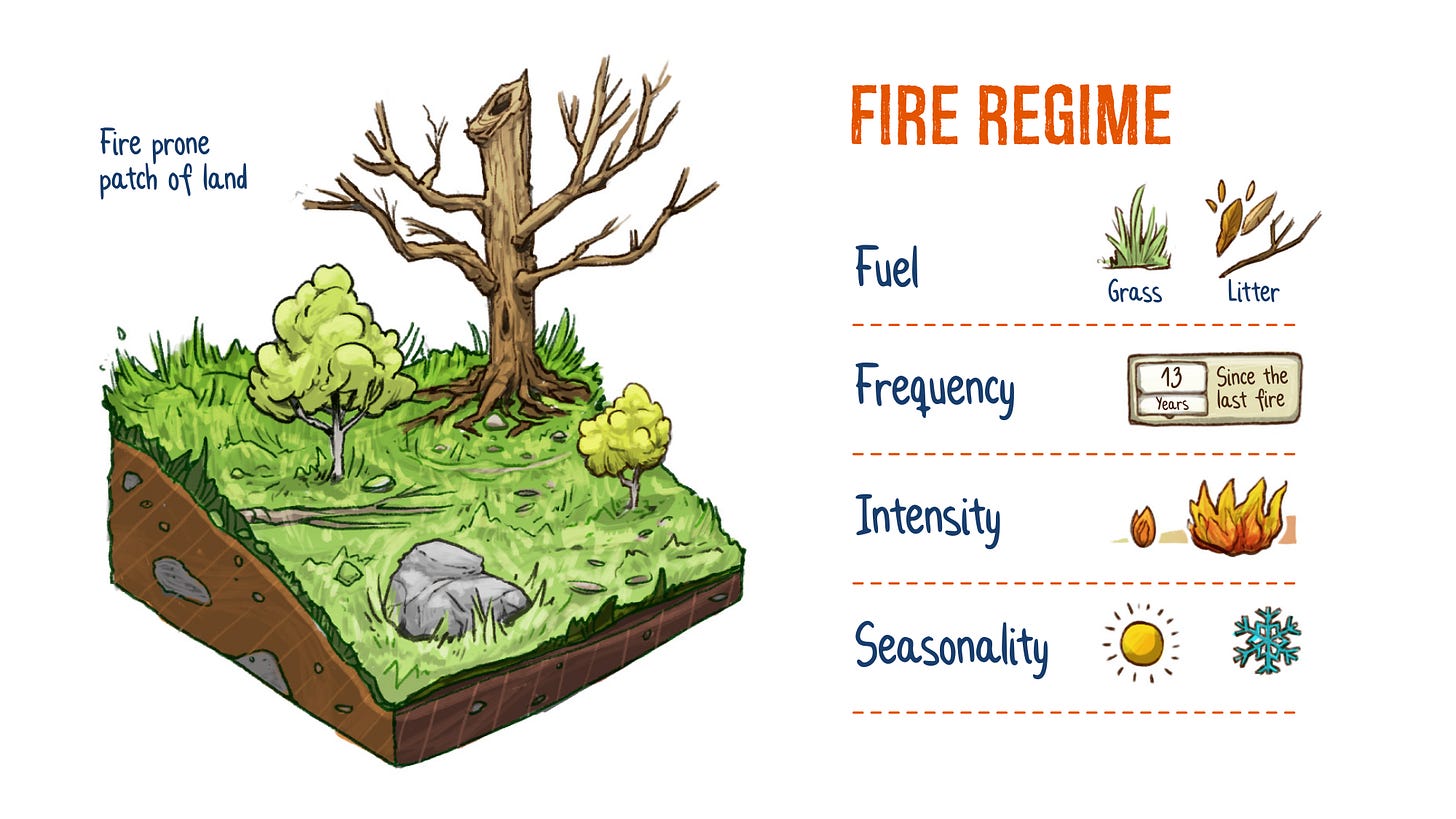

Fire is local. The local landscape is where we see and feel fire and its effects. It is also where much of our management levers are located, from fuel management to suppression and community education. There is another good reason for thinking local when it comes to fire, and that is the fire regime concept. It is the idea that any fire prone landscape has its own distinct flavour of fire, including dominant fuel type, fire frequency, seasonality, intensity and severity. These distinct local patterns include not just average conditions, but also variability and extremes. We must be alert to the dangers of reification, but the fire regime concept is a useful counter to another danger, which is the simplistic idea that fire is the same everywhere.

Fire has drivers. Although fire is incredibly complex, it is constrained by four dynamic biophysical processes: the accumulation of fuel; the drying out of this fuel so it is available to burn; the presence of weather conditions conducive to the spread of fire; and an ignition source to set things off. Fuel, dryness, weather and ignition can thus be thought of as drivers of fire. Without all four drivers, there won’t be a major landscape fire. These drivers are like switches of a circuit that all need to be in the ‘on’ position for big fires to occur. Different fire landscapes – different fire regimes, if you’ll indulge me – are characterised by differences in the patterns of these drivers, including which of them is in the ‘on’ position least frequently and is thus potentially most influential in driving overall bushfire risk.

Fire is risky. I probably don’t need to say much about this idea, because it is the perceptual frame of fire that fits most snugly for many of us, the media included. Still, it is worth highlighting the power of risk as a concept. It invites us to consider all the things we care about that are affected by fire, how likely (and costly) it will be for fire to affect them, and how cost-effective (and risky!) our attempts to reduce risk are.

Fire is cultural. Us humans and fire go way back. Stories around a campfire. Barbecues (did anyone else’s mouth just start watering?). Lighting a candle, rather than cursing the darkness. Nowadays you won’t get far in understanding fire if you don’t include humans in the equation. We start fires, we put them out, we make laws and institutions, and we study fire. All eight billion of us bring a unique cultural lens to fire. Here in Australia, diverse and complex cultural fire practices have been a part of Indigenous peoples’ care for Country for tens of thousands of years. Fire is part of the history, lore and cultural practices of First Peoples all over the world.

As the earth warms and our fire regimes turn feral, we urgently need fresh perspectives. We need to cross disciplinary lines and build bridges between organisations, sectors and communities. We need to listen deeply, especially to those who have held fire knowledge the longest.

Are we up to the task? With the attention economy in overdrive, we can barely sustain focus on our most pressing problems, let alone confront them in all their complexity. Can we snap out of our collective stupor? Does one simply wake a sleeping society?

What we need is something that can hold our attention, that reminds us who we are and that is seared deeply into the human psyche. Eleven years ago, fire effortlessly reminded me what mattered most. Today, I believe fire itself is one of our best hopes for shaking ourselves free of distraction and blazing a trail to a more sustainable future.

I reckon your 6 ideas about fire just gave you the headings for the 6 chapter book. I'd but it! If you haven't already, check out Michael Pollen for a writer who really neatly hangs the exploration of a single topic around a few simple ideas.