The fire to end all fires

Just how big can a wildfire get?

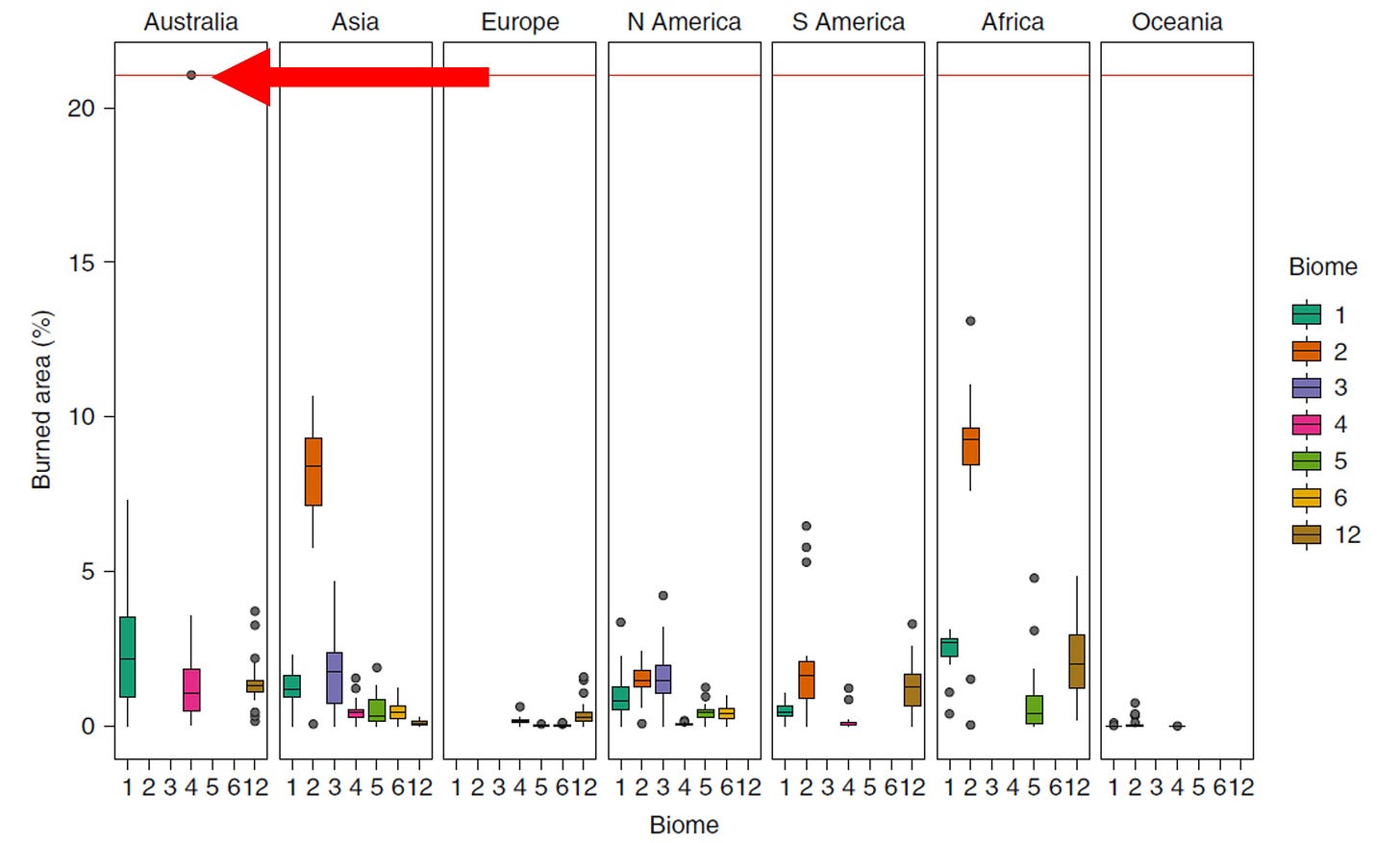

The 2019-20 Australian fire season set many records. One of the most striking, in my opinion, was from a paper by Matthias Boer and friends, that showed the remarkable percentage of temperate forest that burnt compared to other global forest types (‘biomes’) over the last twenty years or so. I use this in presentations and put a big red arrow next to it for emphasis.

Over the last couple of decades, it has been very rare for over five percent of a forest biome anywhere on earth to burn in a single season - unless you’re in the African or Asian tropics, in which case the number hovers around 8-9%. Over 20% of Australia’s temperate forests burned during the Black Summer, a figure that leaves the previous record of about 4% for dead.

That’s a proportion. What about absolutes?

During the 2019-20 season the Gospers Mountain fire, dubbed The Monster, set a new record for the largest single-ignition forest fire in the modern fire management record in Australia - about 500,000 hectares. That’s around 1.25 million acres, or over 700,000 football fields, if that helps you picture it.

When we tell the story of the fire behaviour modelling research behind the Prescribed Burning Atlas, we say we set the size of our case study landscapes at about 200,000 hectares, because that’s about as big as an individual wildfire can get. Oops.

The Guiness Book of World Records, if they are to be trusted, put the biggest single forest fire in the world at 1.2 million hectares, a tie between the Chinchaga fire of 1950 in Canada and the Great Black Dragon fire of 1987 in China .

Of course, perhaps it’s misleading to speak of a single fire. We all know a single swallow does not a summer make, so shouldn’t we be asking about the biggest fire season? We move here quickly from the hundreds of thousands to the millions. In our recently published chapter of the new Black Summer and biodiversity book, we take a tour of some other recent massive fire seasons around the world. The Indonesian peat fires of 1997-98 hit 10 million hectares. The Siberian boreal forest fires hit 13 million hectares in 2019, then nudged past 14 million the year after.

Before I get thrown out by my grass fire-studying colleagues, I should acknowledge the eyebrow-raising figures associated with savanna and grassland fires. Around 20% of Australia’s savanna region burns each year - just under 20 million hectares. The 1974-75 fires followed a couple of years of La Nina-inspired fuel growth, so the figure grew much, much higher. Something like 45 million hectares burnt in the Northern Territory alone.

Let’s stick with forest fires for now because I know more about them (if you’d like a slightly more objective fact, we’ll focus on them because they’re rare and intense). What would it take to put some bounds around the estimate of the biggest ever forest fire and forest fire season?

Let’s start by following Boer et al. and limiting our search to a particular kind of forest in a particular kind of region. It’s not really fair if we count the same type of forest in two different parts of the world, nor if we count two neighbouring but wildly different forest types. We might like to use the typology developed by Keith et al. for the IUCN, which says there are two forest biomes (tropical and subtropical forests, temperate-boreal forests and woodlands) and ten ‘ecosystem functional groups’ within those two biomes. The ecosystem functional groups have names like ‘Tropical-subtropical lowland rainforests’ and ‘Temperate pyric sclerophyll forests and woodlands’. Let’s pick a forest within one of those groups.

If we’re going to find the biggest fire, we probably need to look for the biggest forest. The Amazon is big, 500 million ha or so. What about boreal forest? There’s probably three times as much of that as the Amazon, although it’s also spread out over a bigger area including multiple countries.

It may not happen often, but every once in a while, the boreal must have fires that put those in recent years to shame. How big a proportion of them might burn in the biggest fire season in their history? If Aussie temperate forests can go from 5% to 20% in an anomalous year, what about other forest types? Could they get up to 20%? Or even higher? How high is too high? Even the Amazon is likely to have had some massive fires in its long history. How big did they get?

But hang on a second, haven’t the earth’s forests expanded and contract over time? And hasn’t the earth’s climate warmed and cooled over time? Haven’t oxygen levels in the atmosphere also fluctuated? You can see where I’m going here.

We need some paleoecologists to help us map earth’s ancient forest types. We need some paleoclimatologists to tell us what the climate and atmospheric composition was like at the various stages of these forest distributions. And then we need to put them on top of each other (the maps, not the scientists).

My embarrassingly uneducated guess is that all we need to do is find the hottest, driest and most oxygenated periods in earth’s history, find the biggest forest during those scorchin’ years, and hey presto - there’s your biggest ever fire and biggest ever fire season to boot. Or maybe we start with the biggest forests and then look for the hot years. We could try both. I’m not quite ready to put numbers on any of this. What about you? Before you do, though, remember: this is the biggest fire in Earth’s whole damn history. So it better be a big one.

This might all seem like a bunch of ignorant time wasting. But I say there is some rhyme and reason to it. We hear the call from time to time that we must coexist with fire. To do this, we need to know fire deeply. We need to know about typical fire, sure, but we also need to know about atypical fire. Extreme fire. Maybe even the most extreme fire ever. Just as humans might like to know about the biggest earthquakes or floods that are likely to happen in their area, we should be able to tell them about the biggest fires that could happen - because they have happened before.

The 2019-20 fires changed what we thought was possible in the realm of temperate Australian forest fire. Maybe it’s time to find out what else is possible.