The policy makers were desperate.

This had been the worst fire season yet. Over one million hectares of forest, woodland and grassland burned. Countless plants, animals, fungi and protists were affected. So too were the bacteria and archaea. Even the viruses and prions did not escape the fire’s path. Smoke filled towns and cities. Homes were lost, industries were hit. Firefighters were exhausted. Tragically, several people lost their lives.

They thought they were prepared. Previous seasons had also taken a heavy toll. Scientists had already delivered warnings. Fire managers had already made plans. But the force of the fires was overwhelming. Everybody’s actions helped, no doubt. Things would have been much worse without the collective efforts of thousands of people. But this was cold comfort. Life was measured by what was lost, not by what could have been lost but was saved.

The policy makers were desperate.

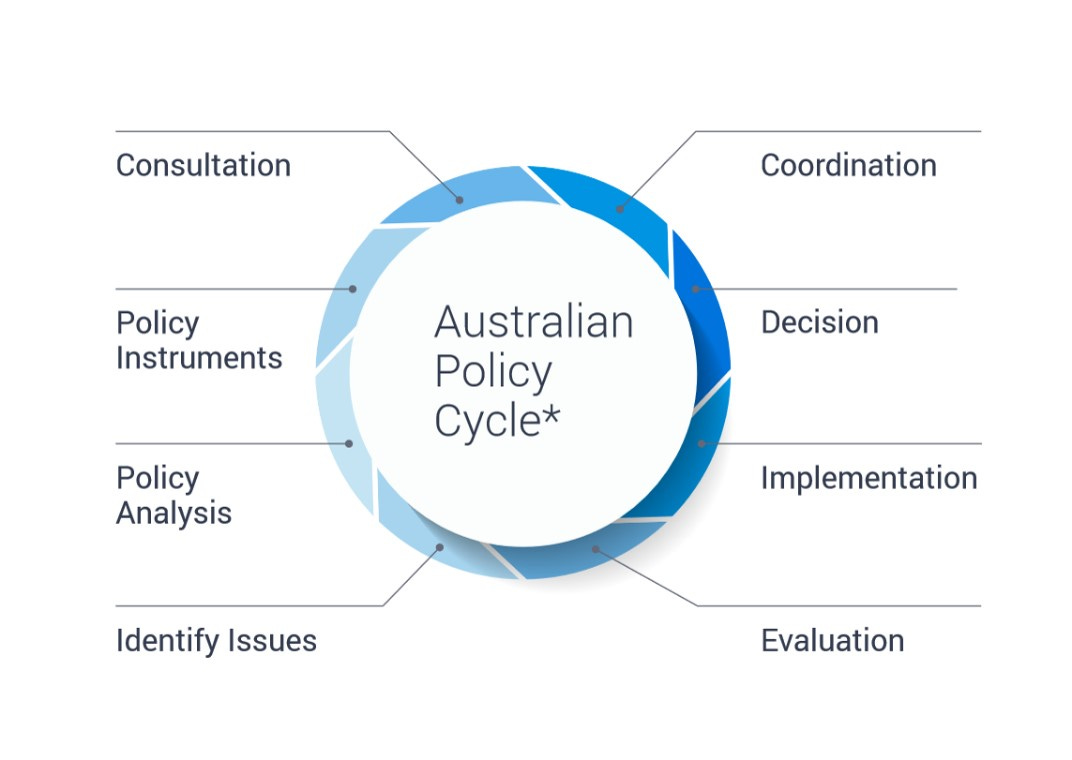

Despite strictly following the steps of the policy cycle, things seemed to be getting worse. Before, they were confident that they were heading in the right direction. When naysayers pointed out that heading in the right direction was necessary but not sufficient, the policy makers grew impatient. “What more do you want?”, they asked. “To travel in the right direction fast enough to actually reach the goal!”, the naysayers replied. “We know we’re not going as fast as you’d like,” the policy makers retorted. “But believe us, we can’t go any faster! Our path represents the balance of many forces, some invisible to you uppity outsiders. We have striven earnestly and conscientiously despite many obstacles. It might seem obvious to you, but if you knew what we know, you’d think differently. You’d see that we are on track.”

But now the policy makers were desperate. “Who are we kidding?”, they lamented. “We’re not on track! We have dutifully followed the principles of the policy cycle, but things are getting worse!!” The policy makers decided to consult a Sage well known to the fire research, management and policy community. They lived in a cave in the mountains and were widely regarded as of unsound mind. But desperate times called for desperate measures. And besides, what could they lose?

They set off on the trek to the Sage’s cave. Siri only took them so far. Soon they had no reception and no vehicle, relying on the mumbled directions of local youths and faded signs that seemed to swivel in the wind. After three days of hiking, they came upon a cave. A cool, dry smell emanated from the gloom. Then the wind changed and a pungent odour arrested their nostrils. It was the Sage. Disheveled, straggle-bearded but with clear piercing eyes, the Sage approached them with a staff and began to beat them.

“Stop it, you maniac!” they cried. “We are here to ask for your help!” The Sage relented and retreated into the cave. Before long a sweet smell emerged, as did the Sage with a kettle of tea for the travelling policy makers. As they sipped the tea, they told the Sage of their troubles.

“Is it our policy analysis that is at fault? Do we need to do more consultation? Is it better policy instruments? We know our evaluation is kind of crappy but we’re doing our best - should we do more of that?”

The Sage remained silent. They entered the cave again and after a good 10 minutes came back with a box of pineapple donuts, just like the ones you used to get in the canteen outside Fisher Library at the University of Sydney. They all partook and when they had finished there was not a single crumb on the floor. At last the Sage spoke.

“You want to know how to solve with worldwide wildfire crisis.”

“Yes!” they cried in unison.

“You are good policy makers,” they said.

“Thank you,” said the startled policy maker, “I wasn’t expecting to get a bit of positive feedback, given all the things people say -”

“Don’t interrupt me!” they shouted, rapping the policy maker on the knuckle with their staff.

“You are good policy makers. You have been true to the principles of the policy cycle. But you are terrible at achieving your professed goal of living in harmony with fire.”

The policy makers averted the clear gaze of the Sage and looked to the ground.

“What makes you think you can bring about such harmony?” the Sage continued.

“What power do you have?”

The policy makers responded confidently that they coordinated the statewide rollout of sophisticated tranches of policies.

“You are one cog in a giant wheel,” the Sage replied.

"What influence do you have?”

The policy makers responded slightly less confidently that they engaged closely with fire managers, researchers, communities and other stakeholders.

“You are one voice among many. Some trust you, some hate you, most ignore you,” the Sage replied.

“What understanding do you have?”

The policy makers hemmed and hawed about risk, fire regimes, threatened species, cost-effectiveness and other important-sounding words.

“You know a little about fire, fire management and climate change, it is true.”

One of the policy makers silently pumped a fist.

“Just a little.”

“What do you know of harmony?”

After a pause, a policy maker furtively proffered “You mean like general equilibrium theory in economics?” The Sage reached for his staff but withdrew his arm as he doubled over in laughter.

“Thank you for answering my question. I need to take a nap now. Leave me and don’t come back until the sun becomes the moon, the dirt becomes the air and the forest becomes human.”

The policy makers looked at each other, perplexed. The Sage reached again for his staff and the policy makers quickly got up and ran away.

“What do we tell the boss?” one of them said.

“I forgot to ask the Sage for a receipt” said another.

“Does anyone else smell smoke?” said the third.

Who were those policy makers?!?

Bureaucrats? Experts? Elected officials? 'Other stakeholders' (aka everyone else)?

Either way I love the parable (it it's a parable!) - a bit of violence, bit of humour, just to help the stark reality go down.