A few years ago I attended a workshop on developing conceptual figures at the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, at Western Sydney University. I was drawn to it for several reasons. I love science communication. I love learning. And I love free food. I can’t recall what we ate, but over the course of a few hours we got into the whys and hows of creating figures to convey important concepts in our work. I wasn’t particularly good at it (and am still not), but that didn’t stop me enthusiastically discussing the topic with colleagues as we sat at our tables sketching away on butcher’s paper.

To this day I remain convinced that coming up with new metaphors and graphics could genuinely deepen our understanding of wildfire, provoking new insights amongst expert and layperson alike. As part of the brief I’m preparing for some talented designers to help me communicate wildfire risk and climate change (Item #11 on my to do list), I sent them a few of the kinds of figures that have cropped up repeatedly in talks I’ve given over the years. Things like Mercator projections of satellite fire detections, combined vegetation and climate zone mapping illustrating Australia’s fire regime niches, concept figures showing various properties of the four biophysical preconditions of fire, multi-coloured bar plot time series showing the erratic but relentless rise in extreme fire weather conditions, little cartoon icons representing things that get consumed by fire, like houses and electricity infrastructure (on reflection perhaps not the best way to communicate such a serious topic (says the guy who invented the four friends of fire)).

I’ve occasionally thought about starting a discussion series on the topic of visual science communication. We could call it That Figures or some other awful pun, and bring in examples of figures that have caught our eye. Maybe they tell an incredible story, maybe they adhere to Tufte’s principles, maybe they showcase some new coding wizardry or a beautiful colour palette. Or maybe they’re just unspeakably awful. Perhaps I will live to see the day when pride of place on the great mantle of scientific publications is taken by a journal dedicated to the art of visual science communication (I’m really setting myself up here, there are probably already a dozen), with beautiful cross-fertilisation of ideas and artforms between scientists, artists, illustrators, designers, semioticians and overpaid consultants.

When I’m not trying to dream up my own new images or daydreaming about far fetched image discussion fora, I scour the ceaseless tumult of journal articles that crosses my screen, playing the part of conceptual figure connoisseur. Lo! Is this some new delectable diagram? Nay, ‘tis but ho hum standard fare, leaving me unsatisfied and mildly queasy.

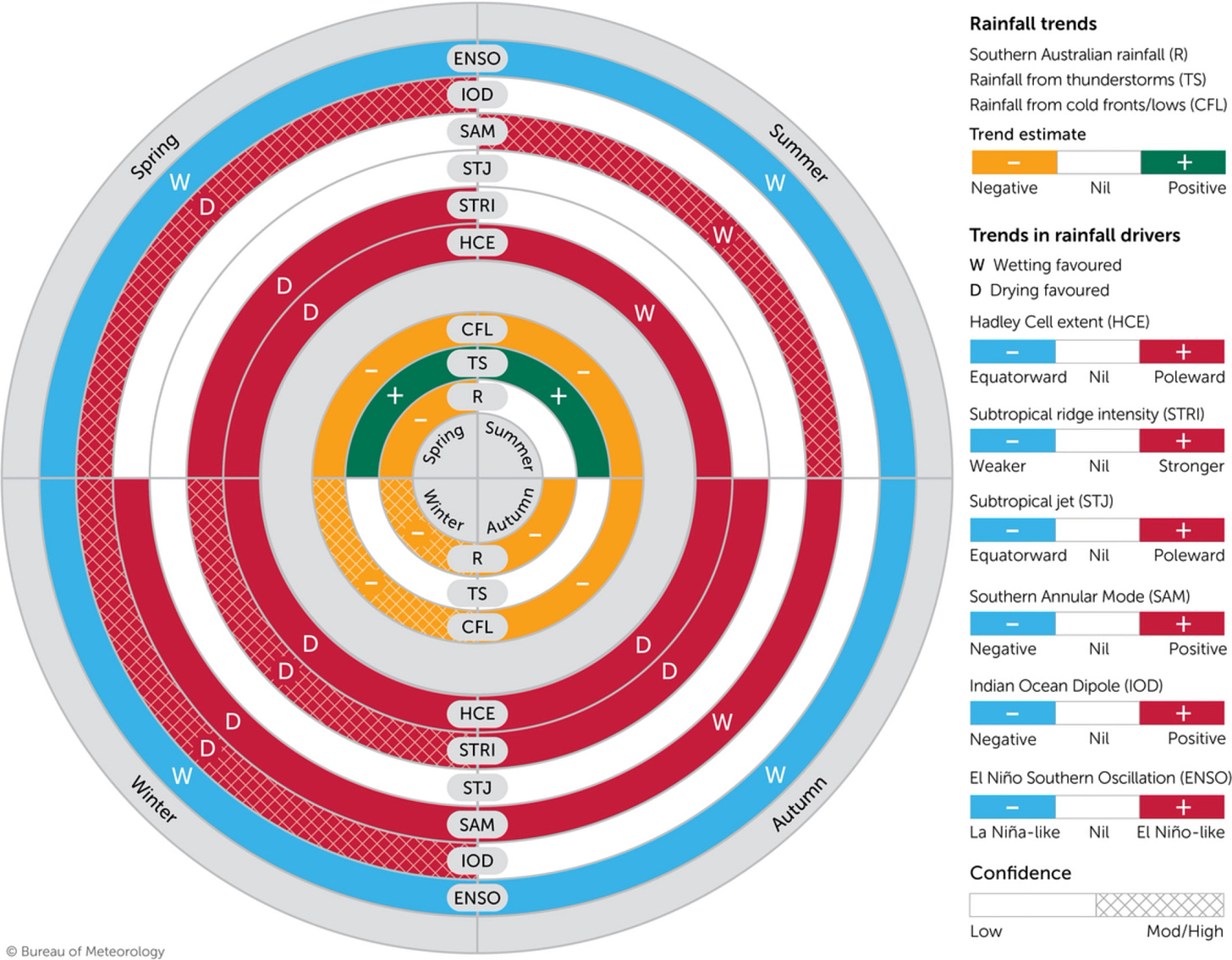

All of which is to say that I stumbled across a paper by Roseanna McKay and colleagues about recent declines in southern Australian rainfall and whether we can explain them. Check out the paper, please, there is an embarrassment of riches in there, including an excellent concept figure of “the weather systems, large-scale atmospheric circulation, and main climate drivers that influence southern Australian rainfall.” So if the paper contains an excellent concept figure, why am I not showing it here? Well, dear reader, before I got to that one I was hit by the following rather extraordinary figure:

The first of the seven sentences that make up its caption reads “Summary of southern Australia rainfall changes and drivers, where concentric circles show 1979–2019 trends in each link of the rainfall-variability chain from small- to large-scale.” The figure appears in the graphical abstract (these usually suck, by the way, but are an excellent home in waiting for the wonderful concept figures of the future).

It’s hard to know where to start with Figure 5 of McKay et al. (2023), so allow me to offer a loosely edited transcript of my inner dialogue.

Wow! I need to take a closer look at this.

Hmm, could this be a way of showing changes in the seasonality of the drivers of wildfire risk?

What the heck is going on here?

This is like one of those artworks that you need to let just wash over you, without trying to interpret it. [glances at it then walks away for 15 minutes before returning]

Oh my God. There is so much going on.

What pops? Mostly red, which means…hmm, lots of different things but not actually drying, that’s the.. the letters, which… okay so there’s a fair bit of drying, particularly in winter and also spring…

In what sense are poleward shifts of the Hadley Cell and the Subtropical Jet analogous to positive phases of the Southern Annular Mode, the Indian Ocean Dipole and El Nino-like conditions (and hence coloured red)? Damn I’d better read the paper…Hmm still not sure, my lack of climatology is showing… maybe I can ask one of the authors.

Wow and there’s inner ones too! Total rainfall, thunderstorms and cold fronts/lows. Decreasing rain all year round except for summer, huh?

Great Odin’s Raven! There’s hatching as well! Okay, all of the reasonably significant trends are red… but not all are wetting… Oh and there’s hatching on total rainfall and rain from cold fronts and lows in winter, I missed that at first…

And why are the seasons enclosed in their own grey bars around the outside? Surely a label would do.. Then again, they do match the inner labels this way…

If they’re trying to honestly represent complexity, then by Jove, they’ve done it.

Perhaps if we added a third dimension… Ha, that almost never works… but maybe this time it will…

Wow, I’ve barely scratched the surface.

What confidence and courage to even try this!

Could I adapt this? Learn from this?

It’s wonderful.

It’s madness.

It’s genius.

It’s definitely too much.

Or is it?

This may be a fair characterisation of the (local) weather, but it does not capture the drivers of the (global) climate, or of climate change. The distinction between climate and weather is an important one.